And Some

Came Back…

The story of a Bomber Crew

with 149 (East India ) Sqn. R.A.F.

by

Alan Fraser

149 (East India) Sqn Historian

In the dark war years, young men from Britain and the dominions volunteered for service in the RAF. They did their training, worked hard and went on to a Bomber squadron. Perhaps not the dashing, glorious job they had in mind when they joined, but a vital one never the less. They formed into crews, each one relying on the others to do their job. If one failed then they could all die. Many went out, never to return – and some came back…….

The ‘Woolley’ crew.

The full crew were:

W/O Woolley L C Pilot

Sgt Oddy D W Bomb Aimer

Flt Sgt Edwards D Navigator

Sgt Rollo T Flt Eng

Sgt Wray F W Wop

Sgt Pollock W P MU Gunner

Sgt Murray J P Rear Gunner

The Squadron.

"As war approached, No 149 (East India) Squadron, which had served briefly in World War I, was re-formed in 1937 at RAF Mildenhall as a night heavy bomber unit. It was initially equipped with the last RAF heavy bomber biplane, the Handley Page Heyford, but not for long. In early 1939 these were replaced with the new, geodetic structured Vickers ‘Wellingtons’. Designed by Barnes Wallis, of Dam Buster fame these were sturdy, reliable aircraft which could absorb a great amount of damage and still return home.

Wellington 1c of 149 Sqn – source unknown

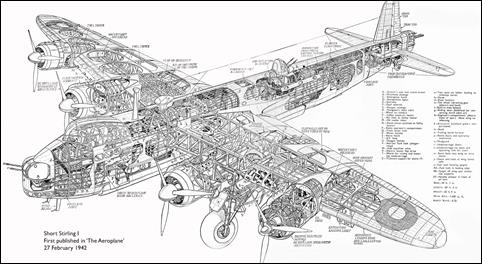

Then along came the mighty Short’s Stirling Aircraft. Various constraints had turned the original design into an aircraft which was badly behaved on the ground, being very manoeuvrable at low and medium altitude, but sadly deficient at its operational ceiling of twelve to fifteen thousand feet.

Looking a bit like a bulldog, with exceptionally long legs at the front, the Stirling either was loved or hated….most of the crews loving it. The aircraft served 149 Sqdn right up until its withdrawal from mainstream bombing in 1944, due to unacceptable losses when employed in this role. This did not prevent its use where its strengths were a distinct advantage.

Because of the Stirling’s deep wing and short span it had very good manoeuvrability at low levels. So the life of the Stirling was extended on Mining Operations and made it ideal for what were called ‘Special Operations’. The latter involved late night flights into Enemy Territory at low level to drop supplies, ammunitions and Agents to the Marquis and other resistance groups. Mining involved flying accurately at Low and later High level to place various types of Mines in selected waters around occupied Europe.

There is more written about these flights at the appropriate place in the catalogue of Operations undertaken.

After moving to Methwold the squadron finally started re-equipping with the Avro Lancaster Mk 1. This iconic Bomber was to take the Allies through to the end of the war and beyond. The re-equiping meant that the squadron became, in effect, split into two. One part operated the Stirling in the Mining and ‘Special Ops’ role, the other used the Lancasters and G-H to accurately bomb all targets.

It did not stop the use of the versatile, low level bomber that was the Stirling. Both of these aircraft types operated out of Lakenheath with 149 (East India) Squadron and also detachments at RAF Chedburgh with the Squadron. The majority of the ‘Special Ops’ in this account were flown from RAF Chedburgh in the Stirling aircraft.

149 (East India ) Squadron Aircrew in 1944 at Methwold in front of a Lancaster.

War Time RAF Service.

Most combatants joined the Royal Air Force as volunteer reservists (VR) during the 1939-45 period. For initial training they were sent to an RAF ITW or Initial Training Wing. At the start of the war, most pilots and observers were commissioned officers or senior NCOs. The people who flew as gunners and radio operators were normally taken from the ranks of the 'Erks' on a squadron. Aircraftman 1st and 2nd class (AC1 and AC2) manning the guns and/or turrets and the radios were the 'norm'.

As the war progressed and aircrew were shot down and captured, the authorities decided that they should make all flight crew a minimum rank of Sergeant, ostensibly to ensure that they were correctly treated if captured.

Basic Training

Aircrew Initial Training would have been at an ITW (Initial Training Wing) at one of the many camps which had sprung up. Here they would have been subject to the normal one or two days being kitted out, getting injections and being examined by a doctor or dentist. This was followed by the usual five to eight weeks of Basic Training, which was more directed to making the airman into a soldier rather than an airman. Here, aircrew cadets learned to march, did lots of PT and went to classes. They were usually accommodated in requisitioned boarding houses and hotels. ‘Permanent staff’ were billeted in boarding houses and the HQ was usually located in a local hotel.

This Basic Training was initially carried out by regular RAF discipline instructors, of Corporal or Sergeant Rank. It was a great source of unhappiness that the recruits these regulars were training would be the same or higher rank than them in a relatively short time period. After the basic training was accomplished, the recruits were subjected to a 'streaming' process, where their qualifications and more importantly their aptitudes were measured and considered. Initially, these streams were either ‘Pilot/Observer’ or 'the rest', who made up the crew's gunners and radio operators. Later on in the war these streams were divided into ‘Pilot/Bomb Aimer/ Navigator’ (PBN) and 'the rest', who made up the crew's flight engineers, gunners and radio operators.

Pilots.

These crew members were not just the flyers of the aircraft, they were its 'skipper'. This meant that they were required to demonstrate not just the ability to fly, but the qualities required to be the 'leaders' of their crew and have at least a modicum of knowledge of all the crew’s positions tasks and functions.

‘Hank’ Woolley

It is at 26 OTU that we first hear of the crew Pilot, Sergeant ‘Hank’ Woolley, on the 7th May 1943. Less than a month later, Hank was promoted to Warrant Officer (W.O.). Promotion was rapid in the RAAF.

Navigator - The Observer, at the start of world war two, was the navigator and bomb aimer of the crew. As systems developed and navigational aids were increased the actual navigation of the aircraft rose in importance, as did the function of bomb aiming. Navigators and Bomb Aimers eventually replaced the Observer aircrew category, as the workload required of them increased. Navigators were dedicated to the accurate navigation of the aircraft and the use of the various navigational aids fitted.

Air Bomber – This was the man responsible for the releasing of the bombs and ensuring the aircraft was in the right place to cause the most disruption and damage to the enemy.

David Walter Oddy 1923-2001.

Born on the 18th March, 1923 in Bournemouth, Hampshire, David was the only son of Ernest and Ada Oddy. His elder sister Barbara was born in 1920 and his younger sister Rosemary in 1927. He attended school in Bournemouth and at 17 joined Bowmaker, a Financial Services company set up in Bournemouth in the 1920's. Based at Bowmaker House in the Lansdowne, it was initially a Hire Purchase company for motor vehicles.

In 1942 David joined the RAF, along with several of his friends from Bournemouth Grammar School and, after attending at an ACRC (Aircrew Reception Centre) found himself as an attested AC2 (Aircraftman 2nd Class) at No 10 ITW (Initial Training Wing) Scarborough. He was there under training from 18/3/42 to 13/7/42.

He then moved on to the 10 hours of Flight training that all PBN candidates had (His was undertaken at 4 EFTS [Elementary Flight Training School] on Tiger Moths), to assess their innate piloting ability. David was not selected for further flying training but was selected as an Air Bomber and sent to Cumbria to continue his training.

His first official RAF Station after his ITW (Initial Training Wing) was RAF Millom in Cumbria.

View of RAF Millom in the mid 1940’s – source RAF Millom Museum

It had been opened in 1941 as No 2 Bombing and Gunnery School and in 1942 became N0 2 (O) AFU (Number Two (Observer) Advanced Flying Unit). It stayed in this designation until the end of the war. It must be explained that in the early war years there were no Bomb Aimers or Navigators, both roles being undertaken by the aircraft ‘Observer’. This meant that Observers had to be trained in Bomb Aiming and Navigation. To add to their load, Air Gunnery training was also carried out, to ensure they could handle the aircraft defences if needs be. As the war progressed the two roles could not be covered by one crew member and so Bomb Aimers and Navigators came into being. These individuals were so highly thought of that the Aircrew Selection Boards divided possible candidates into P/B/N and ‘Others’. This meant that P (Pilots), B (Bomb Aimers) and N (Navigators) were the pick of the candidates and were expected to reach the roles they had been selected for.

Bomb Aimers were underutilised for much of an aircraft’s flight, so they were also given rudimentary training in Navigation and Air Gunnery, so they could contribute to the aircraft’s guidance and defence.

His first course (No 21 course) was to carry out the basic Air Gunnery Training required of him, and this course commenced on the 12th November 1942 along with the simultaneous basic Air Bomber course. On the 23rd March 1943 David had successfully completed this course and qualified as an Air Bomber (A/B) and was promoted to Sergeant.

Avro Anson Mk 1 – source IWM

During his time at RAF Millom the main aircraft he was flying in was the Avro Anson, with occasional trips in Boulton Paul Defiants to keep his Air Gunnery up to standard.

His next posting was to 26 OTU (Operational Training Unit). These units, although training units, were also available to Bomber Command to make up the numbers for the ‘1000’ Bomber Raids and other duties. Many crews in training were lost on Operational flights.

Arriving at RAF Wing in Buckinghamshire, he was part of the gathering of aircrew for further training on the Vickers Wellington – and the famous ‘crewing-up’ procedure.

This was a strange, but extremely effect way of crews ‘finding themselves’. All the aircrew were put in a hangar or other large hall and told that they needed a five man crew of: Pilot, Air Bomber, Navigator, Wireless Operator and one Air Gunner. This was the basic crew for a Wellington Bomber, although at the Heavy Conversion Unit (HCU) they acquired another Gunner and a Flight Engineer, to bring the total to seven.

They then milled around and talked. Some friendships had already formed, others started at that point. It was very unusual for a crew to be changed after this selection process, although it did happen.

Then the embryonic ‘crew’ settled down to training, both at RAF Wing and at RAF Little Horwood. After successfully completing that training they went to 1651 HCU at Waterbeach, where the crew was completed with the arrival of another Gunner and the Flight Engineer, Sgt Tom Rollo.

RAF Waterbeach. Stirlings of No 1651 HCU in flight. Source IWM.

Flight Engineers.

Flight Engineers came about as a result of the need for an ‘on board’ technical expert to operate the various systems on the Bombers. Coastal Command however, had been flying with an airborne fitter who “double-hatted” as an Air Gunner and the first Flight Engineers (FE’s) were also Gunners, following the Coastal Command idea.

Initially the majority of FE’s were already RAF trained fitters. They attended a 3-week course then went on to do a type familiarisation course on the aircraft they would be crewed on. Once posted to a flying unit, the airmen were given temporary rank of Sgt, albeit in their original trade, and awarded an Air Gunner (AG) flying badge; the “E” brevet not being designed until 1942. Later it was recognised that FE’s didn't all need to be fully qualified fitters or riggers, so it was only later in the war that direct recruiting took place for Flight Engineers.

The training for these recruits was far more comprehensive than for those who were already technically qualified in a trade. As a result, direct entry civilians were accepted in mid-1943. No 4 School of Technical Training (No 4 S of TT) at RAF St Athan was the hub for FE training, with entrants going through courses of varying lengths, according to their expertise on joining.

A Flight Engineer’s course at RAF St Athan

Flying training time was very sparse and it was quite normal for them to qualify for their flying badges without ever having flown in an aircraft!

Tom Rollo was born in Fife, Scotland on the 15th of July, 1921. He completed his schooling at age 14 and served an apprenticeship as a joiner. Aged 19 he volunteered for the RAF as a Fitter (Currently called an Airframe Specialist). After training he was posted to No 222 (Natal) squadron. It was known as ‘Natal’ squadron as it had received funding from the South African government to purchase the Squadron’s Spitfires. His son, Colin, remembers being told that there were two people required to maintain a Spitfire - one looked after the engine and the other the air frame. Tom was the Airframe guy. Of course, when Tom volunteered as a Flight Engineer he had to increase his knowledge scope by adding an Engine course. This would have been in two parts. One was to bring his basic engine knowledge up to speed, the second a ‘type’ course on the Stirling’s Hercules engines.

After qualifying as a Flight Engineer, Tom was sent to 1651 Heavy Conversion Unit (HCU). An HCU was typically where the Flight Engineer and another Air Gunner joined a crew who had trained on Wellington aircraft. On a four engine aircraft the Flight Engineer was responsible for the technical systems on the aircraft, operating the fuel management system and assisting the Pilot during take offs.

An early Stirling

Our crew would now be settled into a team of seven men – a Stirling crew.

On the 8th August 1943, the now fully ‘Stirling’ trained crew left 1651 HCU ready to undertake operations and were posted to 149 Squadron then located at RAF Lakenheath in Suffolk. There were two Squadrons at Lakenheath, 149 and 199, who both operated the now ageing Short Stirling aircraft.

The following is an account from a newly-qualified Flight Engineer, who arrived on 149 Sqn in late 1943. It gives a flavour of the risks these crews were taking.

“My first flight on a ‘Stirling’ four engine bomber was in 1943 and we were airborne for just over two hours. This was with my new crew and the pilot in charge was an instructor; these instructional flights carried on until my pilot and the rest of us were considered ready to go solo. Further periods of daylight circuit work were carried out until we were proficient. On that day we commenced night flying, which would have been with an instructor.

After three hours of circuits and landings we were sent solo, continuing with circuits and landings for an hour and a half. Further night flying training continued on circuit work until we were transferred to another flight for training in cross country day flying. This involved two sorties of just over six hours, followed by night flying exercise of nearly five hours

.

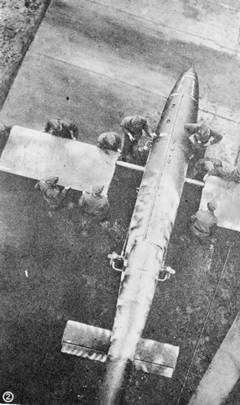

A 149 Sqn Stirling running up at Lakenheath. Source – IWM

The ‘Woolley’ crew.

The initial full crew were:

W/O Woolley L C Pilot

Sgt Oddy D W Bomb Aimer

Flt Sgt Edwards D Navigator

Sgt Rollo T Flt Eng

Sgt Wray F W Wop

Sgt Pollock W P MU Gunner

Sgt Murray J P Rear Gunner

This was the crew for the first eight Operations. After that, Flt Sgt Edwards was replaced with Fg Off. ‘Pop’ Prior, who stayed with the crew until they had completed their tour.

Note :Despite extensive searching of the Station and Squadron ORB the author cannot find a reason for this replacement.

RAF Lakenheath today, with an F15 Strike Eagle taking off.

During their introduction to 149 Sqn they carried out the usual Circuits, landings, fighter affiliation exercises and cross country flights before becoming ‘Operational’. The full “Woolley” crew 149 Sqn Operational history follows. Some crew members did additional trips in other crews.

1st Op - Stirling, serial EH903 coded OJ-R

22nd Aug ’43 Target – Mining – Frisians

2nd Op - Stirling, serial BK711 coded OJ-O

28th Aug ’43 Target – Mining – Frisians

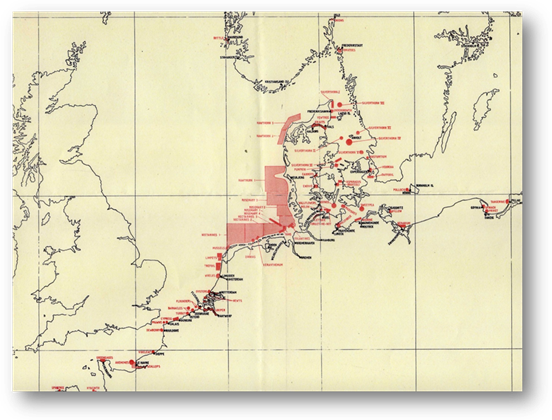

Mine Laying Operations.

Although not as glamorous as attacks on the big industrial cities, these missions were a vital part of the Allies efforts to keep shipping and U-Boats penned up. They were also used as ‘blooding’ Operations for the new crews, to give them a taste of Operations without too much danger. The losses on these raids rapidly alerted the Powers That Be that this was a false premise.The mine laying trips carried out throughout the war were known as "Gardening,” flights and as such, all mine laying flights were given this title. The crews sometimes referred to their mines as ‘Vegetables’.

The Minelaying Code

Antwerp Channel – Juniper Kiel Harbour – Wallflowers

Bayonne – Elderbury La Pallice – Cinnamon

Boulogne – Dewberry Le Havre – Anemones

Brest – Jellyfish Le Havre –Scallops

Cadet Channel – West Baltic – Sweet Peas Lim Fjord (Aalberg to Hals) – Krauts

Calais – Prawns Little Belt – Carrots

Cherbourg – Greengages Little Belt – Endives

Copenhagen – Verbena Lorient – Artichokes

Danzig – Privet Maas and East Scheldt estuaries – Newts

Eckernforde – Melons Morlaix – Upastree

Esbjerg and Jutland Coast – Hawthorn 1. 2. 3. Oslo Harbour – Onions

Fehmarn Belt – Radishes Oslo Fjord (Frederikstadt) – Tomatoes

Flushing – Flounders Ostend – Turbot

3rd Op - Stirling, serial EH903 coded OJ-R

5th Sep ’43 Target – Mannheim - Ludwigshaven

605 aircraft were sent to Mannheim/Ludwigshafen. 34 Aircraft were lost, 8 of them Stirlings. The target area was clear of cloud and the Pathfinders marked it well. Ground markers were placed on the Eastern side of Mannheim so that the bombing of the main force - approaching from the West – could move back across Mannheim and into Ludwigshafen on the western bank of the Rhine.

Author’s Note : The effect was known as ‘creepback’. This occurred as some bomb aimers had a tendency to drop their bombs on the first burning target or target marker they came to, to allow a rapid exit from the area. The creepback on this raid was used to help the objective – severe destruction in Mannheim and Ludwigshafen.

The Mannheim records give very little detail beyond ‘a catastrophe’. More detail is available from Ludwigshafen where the central and southern parts of the town were devastated. 1,993 separate fires were reported including three classed as ‘fire areas’ and 986 as large fires. Over 1000 houses, 6 military and 4 industrial buildings were destroyed and more seriously damaged. 127 people were killed and 568 were injured as well as 1,605 people described as suffering from eye injuries. The low death toll is probably due to the main cities being evacuated at this time.

Author’s Note: It was on this Operation that my Uncle and his crew were lost in EE872 of 149 Squadron. Their normal aircraft was also N-Nuts. It was after they were lost that EH693 was given the coding of N-Nuts and the nose art of ‘The Nuthouse’ – the preferred ‘mount’ of this crew for the rest of their Tour. See HTTPS://www.stirlingpilot.org.uk for more.

Results of bombing raid on Mannheim. Source WW2Today

4th Op - Stirling, serial EE963 coded OJ-N

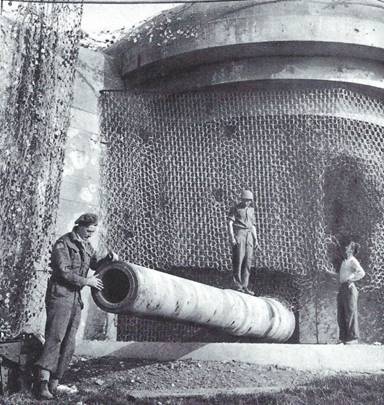

8th Sep ’43 Target – Combined Ops Alperech

This was a joint Operation against the gun positions at Boulogne. The first American Bombers to fly on night sorties were the B-17s included on this night’s Operation. 257 aircraft were in the attack on the site of a long range gun battery. The raid was not successful; the marking and bombing of the target were not accurate and the battery does not appear to have been damaged.

Captured Guns at Boulogne, post-war. Source Unknown.

5th Op - Stirling, serial EE963 coded OJ-N

15th Sep ’43 Target – Montlucon

369 aircraft, including 5 American B-17s, took part in this raid on the Dunlop rubber factory at Montlucon in central France. Pathfinders marked the area accurately and a Master Bomber did the job superbly, bringing the main force in well. Every building in the factory was hit and a large fire started. There is no report of this Operation from France.

6th Op - Stirling, serial EE963 coded OJ-N

16th Sep ’43 Target – Modane

340 aircraft attacked the important Railway yards at Modane, on the main railway route from France to Italy. The marking of the target was not good and the bombing lacked accuracy. No report available from France. 1 Stirling aircraft lost.

A look inside a Stirling

7th Op - Stirling, serial EE963 coded OJ-N

22nd Sep ’43 Target – Hannover

711 aircraft took part in the largest raid on Hannover in two years. This was the first of four heavy raids on this target, and the first time (5) B-17s had operated over Germany. 5 Stirlings were lost. Visibility over the target was good, but stronger winds than forecast caused the marking and bombing to be concentrated 2-5 miles south-southeast of the city centre. Little damage was caused.

8th Op - Stirling, serial EE963 coded OJ-N

23rd Sep ’43 Target – Mannheim/Ludwigshafen

628 aircraft returned to Mannheim to destroy the northern part of the city, which had escaped in the earlier raid. Marking was good and the bombing was well concentrated, although creepback occurred and the bombing moved through Ludwigshafen and out into open country. Many houses and buildings were destroyed, with 25,000 people bombed out of their homes, over 100 killed and over 400 injured. The I.G. Farben factory in Ludwigshafen was severely damaged. 32 aircraft were lost.

9th Op - Stirling, serial EE963 coded OJ-N

27th Sep ’43 Target – Hannover

678 aircraft raided Hannover, but once again, faulty marking meant that the markers were 5 miles north of the city centre. Little damage was done to the target. 10 Stirlings were lost

10th Op - Stirling, serial EE963 coded OJ-N

3rd Oct ’43 Target – Kassel

547 aircraft raided Kassel, losing 6 Stirlings. Yet again, faulty marking (although this time by H2S aircraft overshooting the aiming point by a large amount) caused bombing in the wrong area. This time, however, some good damage was caused to the Henschel and Fieseler (Later, producers of the V-1) factories. Casualties were 118 people dead and 304 injured.

11th Op - Stirling, serial EE963 coded OJ-N

4th Oct ’43 Target – Frankfurt

406 aircraft took part in this raid, with 2 Stirlings lost. One B-17 was also lost and so this became the last night raid the USAAF did with the RAF. Clear weather and good marking meant that this raid produced the first serious blow on Frankfurt so far in the war. Extensive damage was caused in the eastern half of the city and in the inland docks on the river Maine. They were both reported as, ‘a sea of flames’. No casualty figures were released for the raid, but many of the town’s inhabitants fled the city by train in the following week.

12th Op - Stirling, serial EE963 coded OJ-N

30th Dec ’43 Target – High Level Mining, Gironde.

This new method of dropping mines was introduced by 149 Squadron in December ’43 and required different techniques from normal mining. The advantage was that the delayed action mines could be dropped from a greater altitude, reducing the risks to the aircraft from light Flak and small arms fire.

13th Op - Stirling, serial EE963 coded OJ-N

25th Jan ’44 Target – Abbeville

76 aircraft including 56 Stirlings, attacked V-1 Flying Bomb sites in the Pas de Calais and near Cherbourg. There were no losses.

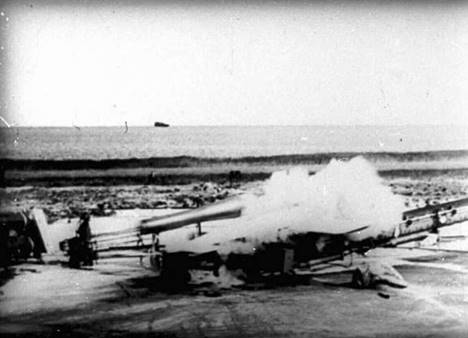

Flying Bombs and Operation Crossbow.

In June, 1942, Germany began working on a new secret weapon. It was called the Fieseler Fi 103, but we knew it as the V-1 Buzz Bomb. The V-1 was a pilotless monoplane powered by a pulse-jet motor and it carried a one ton warhead.

They were launched from a fixed ramp and travelled at about 350mph and 4,000ft with a range of 150 miles.

V1 Flying Bomb

Military intelligence eventually discovered that the V-1 missile was being built at Peenemünde and in May, 1943, Winston Churchill ordered Operation Crossbow, a plan to destroy V-1 production and launch sites. Germany first launched its new weapon from sites at the Pas-de-Calais on the northern coast of France, on 12th June, 1944. The first ten failed to reach the country but on the following day one landed in Essex. Over the next few months 1,435 hit south-east England. These attacks created panic in Britain and between mid-June and the end of July, around one and a half million people left London.

Operation Crossbow.

A V-1 being manhandled up to the launching ramp. Source-unknown.

By the late autumn of 1943 the Air Ministry set up a new directorate with instructions to co-ordinate all information on 'CROSSBOW', the code-name given to the measures to deal with the flying bomb.

V-1 at Launch

The 'CROSSBOW' sites were situated, for the most part, in woods or orchards. This made it difficult to pick them up at a glance; on the other hand, a wood is an easily identifiable object from the air.

For some reason the Germans made no effort to camouflage their 'ski sites'. Preliminary tests with an instantaneously fused bomb dropped from a height of 2,000 feet gave bad results. It proved necessary, therefore, to descend to tree-top level and land the bomb in the main building, the non-magnetic concrete hut standing near the ramp.

At first it seemed that attempts to do so would be to invite crippling casualties. Very careful routing, however, combined with exact timing minimized this danger. The routing was the most important part of the crew’s briefing, and it was based on information supplied through the army liaison officers and from other sources and kept up to date, when necessary, every fifteen minutes.

A Feisler Fi 103 (V-1) being assembled.

14th Op - Stirling, serial EE963 coded OJ-N

28th Jan ’44 Target – HL Mining Kiel Bay

This Operation was in fact a diversionary raid, designed to draw the German defence aircraft away from a major raid on Berlin. 64 Stirlings were involved and three aircraft were lost.

15th Op - Stirling, serial EE963 coded OJ-N

8th Feb ’44 Target – Special Ops – Tempsford.

This was amongst the first of the ‘Special Operations’ that 149 squadron was to be associated with.

‘Special Operations’.

These new raids were classified as Top Secret (at that time) and involved fairly long low level flights over occupied Europe (in our case mostly France).

149 were involved in supplying the French resistance with the means to carry out their functions, including guns, ammunition and radios. This meant dropping containers from very low level at night.

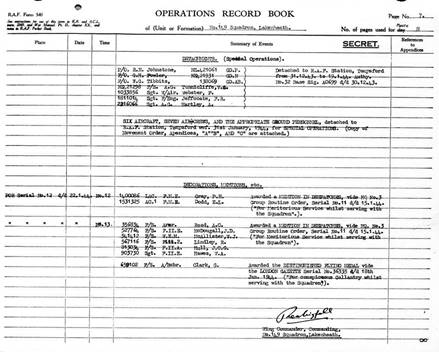

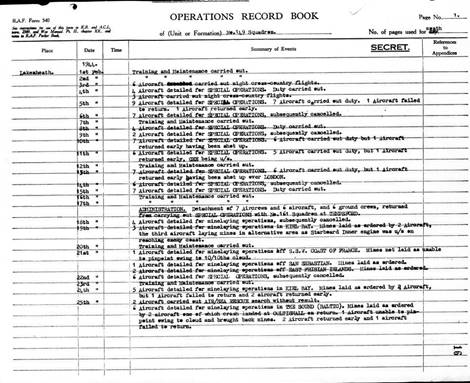

They were carried out only during the Moon phases, before and after a Full Moon, and at very low level - this involved accurate navigation and flying as individual aircraft, often when Main Force bombing was not involved. These trips were made under great secrecy; naturally those at the receiving end of the mission were under great risk. The crews were given the position of the dropping Zone (D.Z.) which would normally be a field possibly three or four hours away in France. If the crew arrived at the correct area and received the correct Morse Letter flashed to them from the ground, they could drop from low level. If the Morse letter was incorrect or not seen, they were normally given an alternate site, otherwise they brought the containers back to base. They would generally find out later why a drop was cancelled, very often the Enemy had broken the Resistance security and was lying in wait. The place and time of take-off was often written in the squadron Operational Record Book (ORB) purely as ‘special operations’ and/or ‘duty carried out’ with no times or locations mentioned. The actual task debriefs were forwarded from the squadron to the Air Ministry under separate cover marked ‘Top Secret’.

The ORB copy shows that several of the 149 Sqn crews and aircraft were detached to RAF Tempsford, the home of 161 and 138 (Special Duty) squadrons, to help with the build up to D-Day and the increased activity in the Resistance and other groups involved. The training of the 149 Sqn crews was started on the 12th of Feb 1944, with the C.O. of 161 being Wing Commander P C Pickard. This was the same person who flew ‘F-Freddie’ in the famous film featuring 149 Squadron, ‘Target for Tonight’. He was killed shortly after 149’s arrival. The training of the crews was successful and they were used for many Special Ops, including operating from their home airfield of RAF Lakenheath after the detachment to Tempsford was declared complete.

16th Op - Stirling, serial LJ526 coded OJ-R

11th Feb ’44 Target – Special Ops

17th Op - Stirling, serial LJ526 coded OJ-R

3rd Mar ’44 Target – Special Ops

18th Op - Stirling, serial EE963 coded OJ-N

5th Mar ’44 Target – Special Ops

19th Op - Stirling, serial EE963 coded OJ-N

10th Mar ’44 Target – Special Ops

20th Op - Stirling, serial EE963 coded OJ-N

24th Mar ’44 Target – Laon

143 aircraft were in this raid to Laon railway yards. 2 Aircraft were lost. The weather in the target area was clear, but the Master Bomber ordered the attack to be stopped after 72 aircraft had bombed. The raid was not a success and the rail lines were repaired the following day.

21st Op - Stirling, serial EE963 coded OJ-N

10th Apr ’44 Target – Special Ops

The following is an extract from the History of the Maquis linked to 149 Squadron:

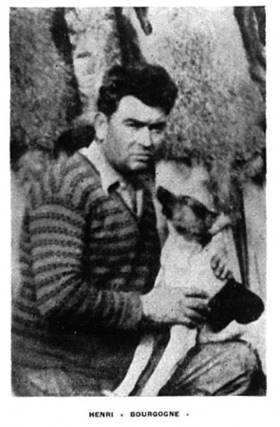

“The leader of the resistance in the region of Semur-en-Auxois was one Henri Camp, carpenter of the city. As with all Resistance leaders and true patriots, the 1940 defeat weighed terribly on his mind, and he thought of revenge and how to prepare for the liberation, which at that time was a long way in the future. His first actions were to organize numerous escapes for French prisoners (more than fifty from the camp Massène near Semur alone), to recover and conceal the equipment left by the Army and take several machine guns to his property for safe keeping.

Henri Bourgogne.

(Group Burgundy)

“(the group)…..Composed of groups of eight to ten men, well versed in sabotage and ambush, the group grew gradually despite many problems. From seventy men in April 1944, one hundred and forty in August and finally reinforced sections equipped with anti-tank weapons and mortars. He (Henri) contacted the Morvan camps, those Auxois (Auxois and Vitteaux groups which, attached to Henri Burgundy, became independent in August 1944) and others.

The Group (Henri) Burgundy had the following tasks and shipments for the winter 1943, to sabotage Vitteaux, Semur, Epoisses and Verrey-sous-Salmaise. They also struck at road transportation and spares supplies. On the 8th February the Group (Henri) Burgundy paid tribute to the airmen killed in Cussy.”

This last was the tribute paid to the crew who were killed attempting to drop explosives and equipment to the Group Burgundy –

It was a crew from 149(East India) Squadron led by Flt Lt H J Colenutt – the first ‘Special Op’ for the Squadron. All the crew lost their lives to a night fighter flown by Oblt. Karl-Heinz Schaffer of 6./NJG4.

Note: It is rumoured that, during the burial of the crew, a local man placed a Free French flag over a coffin and the Germans shot him for it. I have been unable to verify this.

The memorial laid after the war to the patriots of Group Henri Burgundy, of whom 25 were murdered by the Germans late in 1944.

22nd Op - Stirling, serial EE963 coded OJ-N

18th Apr ’44 Target – HL Mining Fehmarn

This was another ‘Special’ mining operation. Little known.

23rd Op - Stirling, serial LJ625 coded OJ-P

28th Apr ’44 Target – Special Ops

24th Op - Stirling, serial LJ625 coded OJ-P

30th Apr ’44 Target – Special Ops

25th Op - Stirling, serial LJ511 coded OJ-Q

1st May ’44 Target – Special Ops

26th Op - Stirling, serial EE963 coded OJ-N

5th May ’44 Target – Special Ops

27th Op - Stirling, serial EE963 coded OJ-N

9th May ’44 Target – Special Ops

A contemporary Short Stirling of 149 Sqn

28th Op - Stirling, serial EE963 coded OJ-N

7th Jun ’44 Target – Special Ops

29th Op - Stirling, serial EE963 coded OJ-N

7th Jul ’44 Target – Special Ops

30th Op - Stirling, serial EE963 coded OJ-N

28th Jul ’44 Target – V1 Site. Foret-de-Nieppe.

199 aircraft attacked two launching sites and Storage areas. All bombing was through cloud, but G-H led to accurate results. 1 aircraft lost.

Their Tour with 149 (East India) Squadron was over. For over fifty five and a half thousand British and Commonwealth aircrew, their lives were over.

During the crew’s war time service they would have been awarded :

The Aircrew Europe Star

The 1939-45 Star

(Bomber Command Clasp to 1939-45 Star shown)

The Victory Medal

They are undoubtedly entitled to the clasp as shown above.

They went with songs to the battle, they were young.

Straight of limb, true of eyes, steady and aglow.

They were staunch to the end against odds uncounted,

They fell with their faces to the foe.

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning,

We will remember them.

Author’s Note - My thanks go to Carolynne Oddy, Colin Rollo (deceased) and the family of ‘Hank’ Woolley. Their association with, and admiration for the crew brought this story to my attention.

References:

Chorley’s BCL Vol’s 1-7.

149 Sqn ORBs

RAF Lakenheath ORBs

Kraken Luftwaffe Archives

Dr. Theo Boiten’s book, “Nachtjagd War Diaries,” Vol 1.

The Bomber Command War Diaries: by Middlebrook & Everitt

The Stirling Story, by M.J.F. Bowyers

‘Strong by Night’ a history of 149 Squadron by J Johnston.

http://www.flighteng.org/

Return to Index

|

Stirling Pilott

Stirling Pilott

Stirling Pilott

Stirling Pilott